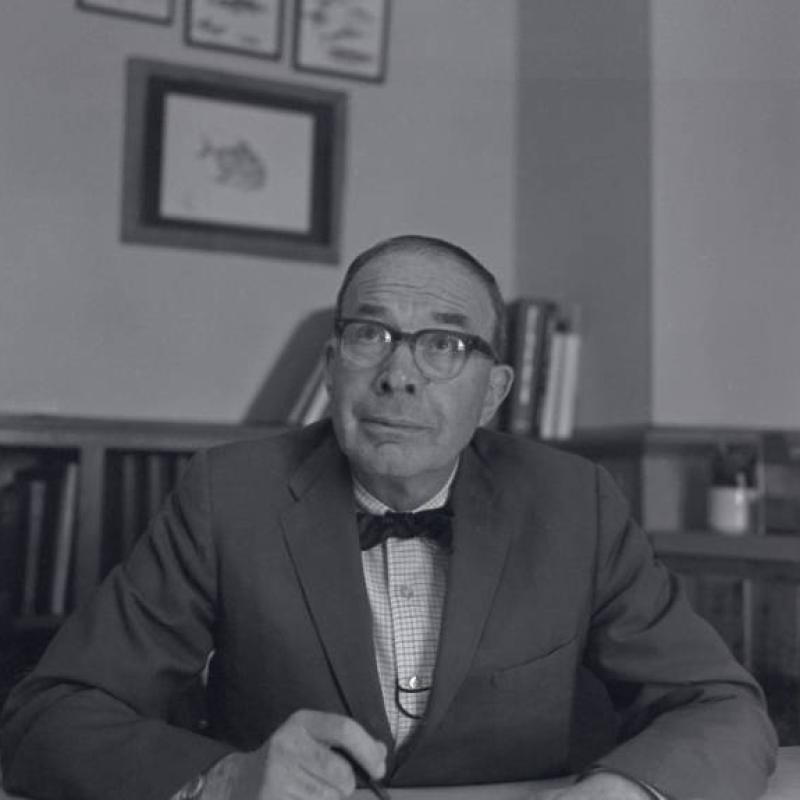

Lionel Albert Walford was born in San Francisco in 1905. The future father of our science laboratory at Sandy Hook, New Jersey, Walford was originally attracted to acting. He attended Stanford University, receiving his bachelor’s degree in biology in 1929. In 1933, he received his master’s degree, and 2 years later his doctoral degree in biology from Harvard University. He joined the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1936 as an aquatic biologist and briefly worked at the Woods Hole laboratory for the Bureau of Fisheries. He then transferred to Stanford University in November 1937. There, he studied Pacific pilchard for the California Department of Fish and Game.

Building a Career

In 1944, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service sent Walford to Washington, D.C. to compile and edit “Fishery Resources of the United States,” published in 1945. In September 1945 he was named assistant chief of the service’s Division of Information. In April 1947, he returned to fishery research and was named chief of the service’s fishery biology branch, a post he held until 1958. During that time, he directed fishery research projects in the south Pacific, off New England and the Mid-Atlantic, and in the Gulf of Mexico. From 1958 to 1960, Walford served as director of the service’s Washington Biology Laboratory.

As the population grew along the coast between Washington and Boston, so did a desire to control pollution and improve fishing. Several conservation groups pushed Congress to establish a marine gamefish research program. The service and Congress agreed and created this new kind of lab, dedicated to marine sport-fish research. Walford had been a strong advocate of the idea, and was appointed as its first director. In just 2 years, Walford fully transformed the facility into a premier sport-fish laboratory on the Atlantic coast. In 1962, he set up a marine game-fish lab on the Pacific coast at Tiburon, California.

In 1963 Walford began to study the distribution of 14 species on the continental shelf from Maine to Texas, expecting to complete the 50,000 mile-long coast survey, county-by-county, in 1965. A similar survey was conducted along the Pacific coast by the Tiburon Lab. When the Walford’s laboratory became a NOAA facility in 1971, he assumed the position of senior scientist and held that post until his retirement in 1974.

Sportfishing Laboratory Makes Major Discoveries

During his tenure as director and senior scientist, Lionel Walford oversaw innovative marine research accomplished by a small staff with a modest budget. The work focused on sharks, a survey of anglers, the impacts of pollutants on marine life, and life histories of game fish–about which little was known.

Walford inspired programs to meet the growing interest of saltwater fishermen. He and his staff provided up-to-date answers to questions about declines in catch and what kinds of factors might support future improvement. He acquired a surplus Air Force boat and converted it into the lab’s first research vessel, named after the British ship HMS Challenger. One of the first projects he assigned to assistant lab director John Clark was a survey of saltwater angling. The survey took advantage of the 1960 census to learn about the number of anglers, where they fished, and their catch.

Pioneering Studies on Bluefish

A major focus of the lab in the 1960s was the bluefish—its life cycle and migration, and its sensitivity to temperatures, light, and food. Bluefish were abundant and a popular target for recreational anglers, but also had a bad reputation as a marauder. Little was known about its life history. These fish appeared in huge numbers in the Northeast in the summer, were caught, and then disappeared until the next summer.

Walford and researchers at Sandy Hook soon began to find answers. Lab biologists and divers Robert Wicklund and colleague Stuart Wilk described a frightening experience they had during a night dive with herring panicked by charging bluefish in a 1966 Sports Illustrated article as “a thrilling and amazing experience.” An earlier 1964 Sports Illustrated article focused on the Lab’s many discoveries despite limited resources and a small staff.

Animal behaviorist Bori Olla was able to keep and observe eight bluefish caught in Florida in a 32,000 gallon seawater aquarium built in the original lab’s basement. There he studied bluefish activity related to light. Olla and colleagues found the bluefish never really rested, but were diurnal, meaning they were most active during the day. Lab researchers John R. Clark and David G. Deuel succeeded in artificially fertilizing bluefish eggs with sperm taken from ripe fish, and studied their migrations by tagging them. They found that there were several local populations along the coast. Walford himself studied anatomical variations in bluefish, believing there were actually two main populations.

Another project enlisted help from local striped bass fishermen who helped tag, release, and report recaptures for a study. It confirmed a large Hudson River population that was linked to the catches in Long Island Sound.

Walford also supported a pollutant study by Ronald Eisler to determine the toxicity of soaps and detergents to marine life. Eisler found some soaps harmless since they could be broken down by bacteria. Those that could be broken down, like synthetic detergents, were the most harmful.

In addition to being the lab’s chief advocate, Walford was also a strong supporter of marine education and citizen science. He founded two of the laboratory’s neighboring organizations. The American Littoral Society was started in 1961 to serve as a bridge between science and the public. The New Jersey Marine Sciences Consortium was established in 1969 to bring colleges, universities, and other groups together to advance knowledge and stewardship of New Jersey’s marine and coastal environment. In 1974 Walford was appointed executive director of the consortium, and continued to work on federal marine grants for New Jersey until his death in 1979.

Advisor on Fisheries, Pollution, Global Warming

Lionel Walford played a major role in the 1963 Conservation Conference, held by The Conservation Foundation, a precursor to today’s World Wildlife Fund. The conference published a major report, one of the first to warn of human-caused global warming. It was written by Noel Eichhorn and based on the work of Charles Keeling, Walford, Frank Fraser Darling and others. Walford was one of 600 leading scientists from around the world to speak at the conference and report research findings. The central topic focused on the worldwide concern of marine life and their coastal habitat.

Walford served on many research committees and was a U.S. delegate, observer, and adviser at international meetings concerning the fisheries of the world. Among those he advised were the International North Pacific Fisheries Commission and the environmental pollution panel of the President’s Science Advisory Committee.

Walford received honorary doctorates from Hartwick College in New York and Monmouth College in New Jersey. In 1960 he was awarded the Department of the Interior’s Distinguished Service Award. He also received the American Littoral Society’s James Dugan Memorial Award.

Officemate, Colleague of Rachel Carson

Lionel Walford was an esteemed biologist but also a prolific author. Well-known for his book, The Living Resources of the Sea, published in 1958. During this time he shared an office with and mentored Rachel Carson. Carson was a science editor at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, parent agency of the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife. Workers there considered Carson their “patron saint” and “perhaps the finest editor the government service ever had.”

Carson and Walford, who was director of the service at the time, joined forces to argue for higher quality in printing publications that drew the public’s attention to the importance of conservation. They won the argument.

Notable Publications

Other books by Walford include Game Fishes of the Pacific Coast from Alaska to the Equator, first published in the mid-1930s and reissued in the late 1970s by the Smithsonian Institution. He and Bruce L. Freeman co-authored the Angler’s Guide to the United States Atlantic Coast.

Walford was a member of The Explorers Club, the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, and an honorary fellow of the American Geographical Society.

Walford donated his own papers and books to the library at the federal fisheries laboratory at Sandy Hook, which was eventually named for him. The original library and laboratory were destroyed in a fire in 1985. The fire-damaged building was renovated and a second, new laboratory was built. The new facility is named for James J. Howard, a New Jersey Congressman who fought to keep it there. The new lab was dedicated on Oct. 18, 1993. The renovated space housed a new library that retained Walford’s name. The collection was rebuilt by NOAA Fisheries librarian Claire Steimle with the help of many others.