Stephen Bell has been part of the microbiology team at our National Seafood Inspection Laboratory since 1989. During that time, he’s seen some significant changes in lab operations. Here’s been there from the emergency response after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill to advances in testing equipment that have improved the accuracy of their results.

Which microbes do you test for in seafood products?

We test every product we get for Salmonella. Depending on the product, we might also test for Enterobacteriaceae, Staphylococcus aureus, fecal coliforms, and Vibrio bacteria. For the most part, consuming these bacteria could give you or your pet food poisoning. They can also have more significant health impacts at higher concentrations.

In addition to these specific microbial tests, we also do what’s called a plate count on products that have been at least partially cooked during processing. The goal for that test is to estimate the total number of viable microorganism cells—both harmful and helpful—in the sample. A plate count by itself won’t tell you if the product is safe to eat. But it can help us detect sanitation problems in a manufacturing process. We can also compare the results of plate counts overtime to see trends in the microbiological quality of products.

What are some of the challenges in microbial testing?

One of the biggest challenges we have is timing. Microbes are living things, and they don’t always behave exactly like we expect them to. To be confident in our results, we need to conduct the tests on very specific timelines. Once you add the product to the test medium, you have to wait around 24 hours to conduct any tests. That’s how long it will take for bacteria in the samples to grow. Testing too early or late could give you a false result. The bacteria could be either too immature to detect or they could have started to die off.

How have the methods you use to test for bacteria changed since you joined the lab?

Things have changed pretty drastically. When I started, our Salmonella test spanned five days. First you’d have to extract any Salmonella cells from the sample. To do that, we’d put the sample in a broth to grow the microbes, let that sit, put it in another broth, and let it sit again. On the third day, we’d streak the microbes we’d grown over the agar in a plate. If the agar turned a specific color, we’d put the bacteria in two other media the next day. Those media were also specifically designed to change color or produce a gas if Salmonella was detected. If you had a positive test after all of that, you’d do it all over again to confirm. It could take two weeks to get a confirmed positive.

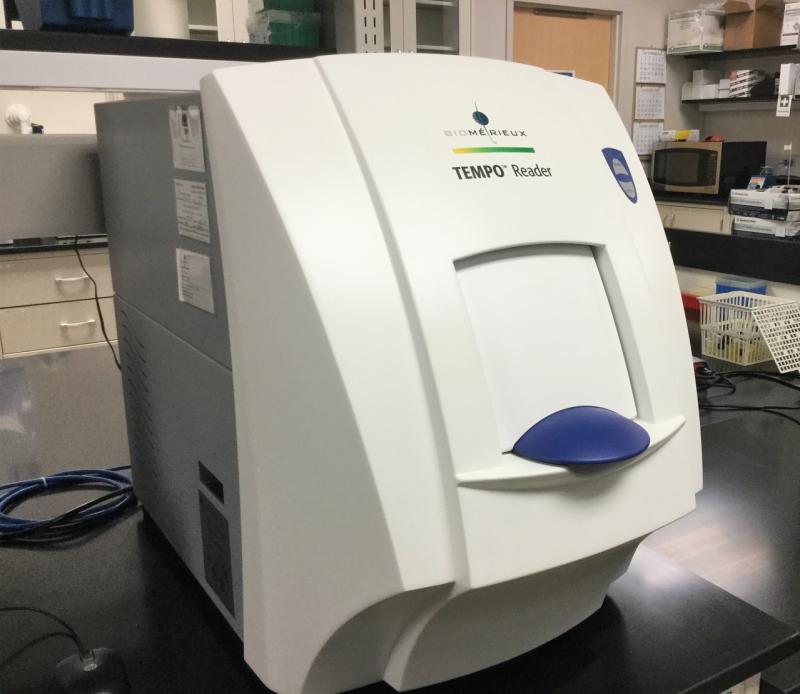

Now, we put the sample in a broth overnight and run that through a machine that’s designed to separate and amplify Salmonella DNA from the broth. If the machine detects Salmonella DNA, we’ll grow that up overnight and run the test again to make sure the DNA isn’t dead. Getting a confirmed positive takes two days instead of two weeks.

You were at the lab when the Deepwater Horizon spill happened in 2010. What role did you play in testing during that time?

We temporarily halted our regular seafood testing during that time so the lab could help determine the impact of the spill. I became the sample custodian. It was my job to keep track of every sample that came to the lab and the results of every analysis we ran. At the end of every day, I’d compile all this information in a report for the White House. That lasted for three or four years.