Chemistry runs in Lisa Price’s blood. Her grandmother, herself a chemist, sparked Price’s interest in the field as a child. She’s had an almost 40-year career in industry and government labs. She’s used her interest and expertise to develop numerous new testing methods for heavy metals.

A lot of your work right now focuses on a new instrument. Can you talk about that?

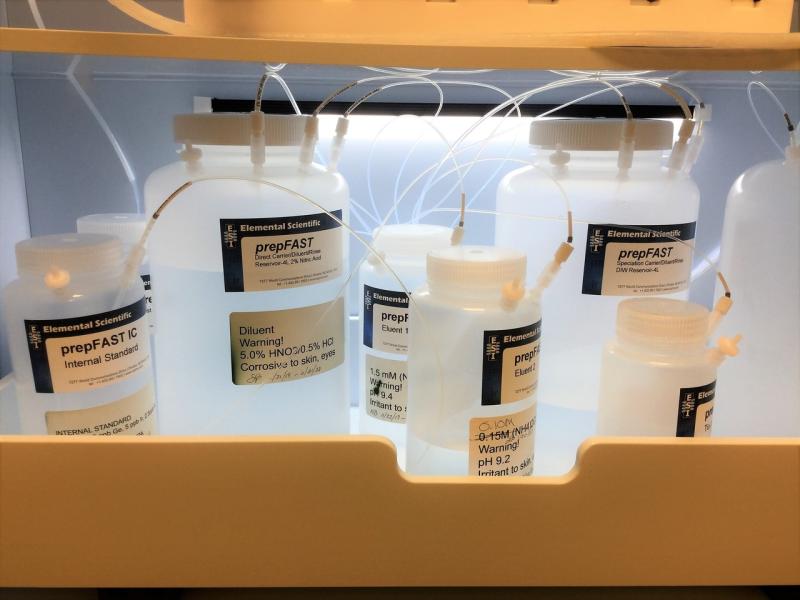

It’s called an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer, or ICP-MS. An ICP-MS instrument can break a sample down into individual elements or atoms and can detect individual isotopes. That allows us to detect metals in a sample even at very low concentrations. That’s important because some metals have negative health effects at concentrations low enough to not be detectable by other methods.

ICP-MS can also detect different forms of the same chemical element—or species. For example, arsenic. The health impacts of arsenic depend on which form, or species, of arsenic is in the product. Other testing methods would tell you if there is arsenic in a sample. But you’d need something like an ICP-MS instrument to determine the concentration and real health risks of that arsenic species.

We expect to begin testing for these different arsenic species at the National Seafood Inspection Laboratory later in 2020.

Because the machine is new to our lab, we are focused right now on validating testing methods using the equipment. We’re in the research and development stage. Ultimately, we will use the ICP-MS to test for mercury, selenium, arsenic, and other metals. But first we have to solidify our testing methods and validate them.

How do you develop a new method?

You typically start with the method recommended by the instrument manufacturer or another nationally recognized entity, like the Federal Drug Administration. You run that through a series of pre-established tests using known quantities of the chemical that you’re trying to detect. The tests are designed to tell you how low of a concentration you can detect with the method or how reproducible the method performs.

As you run through the tests, you make little tweaks to the method based on what you discover. For example, you might get results that show a lower concentration of a chemical than you know was in the sample. If that happens, you go back and try to find where things went wrong. We also make changes to the recommended process based on our specific lab environment or the product we’re testing. Our lab runs a little warmer than some, so we have to make changes that account for that. And certain seafoods have fats or oils that other products don’t have, and those can impact the method as well.

We also consult with other analysts who have developed their own methods. I developed our method to test for selenium using a different technique and instrument. I contacted a professor up in North Dakota who had developed a variation on the method and was able to offer some tips. In the case of the ICP-MS, I travelled to the manufacturer and FDA to go through the methods they had developed with them.

Consulting with others can speed it up, but the process can take several months to a year to develop a method. And once you’ve worked out all the bugs and have a method that delivers accurate, replicable results, you move into validation. That’s a whole other step—there’s method development and method validation.

What advice would you give someone interested in a career in food safety testing?

For anyone interested in food safety testing, I suggest getting at least a bachelor’s degree in chemistry or microbiology. I also recommend that you get as much experience in the lab as possible while in school. That will give you more options and put you in a better position when you start applying for jobs.