Imagine trying to spot an animal that blends in with its environment from an airplane while flying at 150 knots and 1,000 feet up in the air. It's not easy. So, American and Russian government scientists are using infrared cameras that detect warm-bodied animals. This, coupled with high-resolution cameras, locates and identifies seals and polar bears on sea ice in the high Arctic. The use of this equipment helps reduce chances that animals will be disturbed because the survey team can fly at higher altitudes.

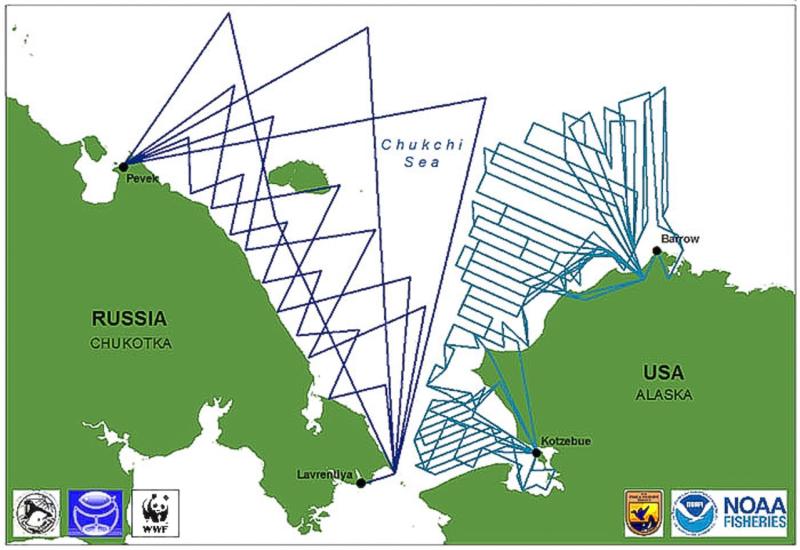

In 2016, U.S. scientists from NOAA Fisheries and Russian scientists from the Russian State Research and Design Institute for the Fishing Fleet collected critically needed information on ringed and bearded seals and polar bears in the Chukchi Sea. The goal was to develop the first comprehensive and reliable abundance estimate of these species.

Bearded seals and ringed seals are vital resources for northern coastal Alaska Native communities and are key species in Arctic marine ecosystems, yet no reliable abundance estimates are available for vast portions of their ranges. Abundance estimates and distribution maps are crucial for sound decision-making about co-management, conservation, and permitting of activities in the Arctic that could affect these species or their habitat.

Bearded and ringed seals, along with ribbon and spotted seals, are known collectively as ice-associated seals because they live on sea ice at times of the year that are important for their reproduction and survival. They use the ice to rest and raise their young. However, because they also spend a lot of time in the water, counting them can be difficult. In 2016, the task of locating these animals was a bit more challenging than usual as Arctic and sub-Arctic winter temperatures were warmer than normal, resulting in an early break up of pack ice. This study focused on ringed and bearded seals as the other two species are not found in the Chukchi Sea this time of year.

“The best way for us to determine how many ice-associated seals there are by conducting aerial surveys during the reproductive and molting period when seals are hauled out on ice and can be detected,” said Peter Boveng. “We need to collect this information so we can evaluate long-term population trends and monitor how these species respond to changes in climate.”

Surveys are being conducted during April to mid-June to best capture when each species is mostly likely to be seen.

During the earlier portion of surveys, scientists have seen mostly bearded seals and polar bears. Beginning in mid to late May, they expect to be locating and counting more ringed seals as the seals emerge from their snow lairs to bask on the ice.

“High resolution cameras enable us to collect color images that we use to identify seal species. This approach allows us to fly at a much higher altitude than previous surveys that relied on human observers looking out the windows to detect and identify animals by eye. We can now fly surveys at about 1,000 feet rather than 400 feet. This dramatically reduces disturbance to the animals we are counting as well as other animals and subsistence hunters in the area,” said Boveng.

In 2012 and 2013, scientists from both countries conducted similar aerial surveys in the Bering Sea. NOAA Fisheries scientists were able to collect over 2.2 million photographs and 5.4 TB thermal video, which helped them better understand abundance levels of four species of ice-associated seals in the Bering Sea. To further minimize the impacts of survey work and ensure it doesn't interfere with subsistence hunting activities, the vast majority of the work will be far from shore and communities.

“Based on our experience from previous surveys, we expect the aircraft to cause very little disturbance. Nevertheless, we will take precautions to avoid disruption of subsistence hunting for bowhead whales, walrus, bearded seals, and other marine mammals. We are actively working to avoid flying over or near the hunting zones around communities,” added Boveng.

Scientists from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also joined NOAA Fisheries on this project. Together the team collected information on another key component of the sea ice community and seal predator, the polar bear. More information on polar bear populations is also of value to Alaska Native communities where the bears are important for nutrition and cultural traditions.

What We Have Seen So Far

During their flights, human observers monitor information sent from the cameras to computer screens in the airplane. A variety of information is displayed including a map of planned survey tracks and a display from each of the three thermal cameras.

Thermal image showing two white/gray "hot spots".

Scientists pair the thermal "hot spot" images with high resolution photographs to identify species. Here is the high resolution photograph that was shot at the same time the thermal image (above) was collected. By zooming in you can see that these two hot spots are actually two bearded seals on the ice.

Myth dispelled! Polar bears can be seen with thermal cameras. It had been thought by some that polar bears were invisible in the infrared, or thermal part of the energy spectrum. These images refute that claim. The image on left is a thermal image. The image on right is a photograph. Red circle in image on the right denotes polar bear, which corresponds with white "hot spot" in left image.

Close up confirming that it really is a polar bear!