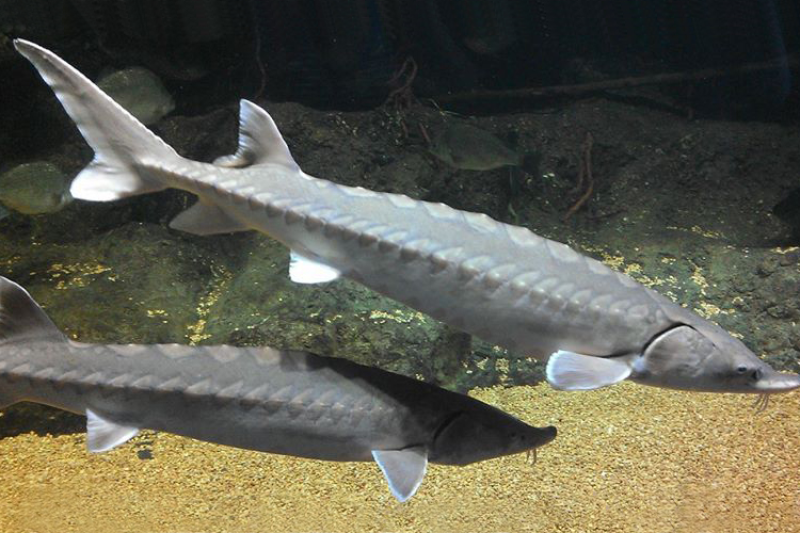

Atlantic sturgeon inhabit rivers and coastal waters from Canada to Florida and can live for 30-60 years. The sturgeon family is the most primitive of all bony fish, with ancestors dating back to the Cretaceous period more than 120 million years ago. Atlantic sturgeon are particularly sensitive to high water temperatures, especially their eggs and juveniles. This sensitivity makes them vulnerable to warming water temperatures associated with climate change.

Beginning in the late 1800s, commercial fisheries began to harvest valuable caviar from Atlantic sturgeon. By the early 1900s, their populations had declined drastically. Recovering Atlantic sturgeon is challenged by their long generational cycles and late age of sexual maturity for reproduction. In response to historic and current challenges, NOAA Fisheries listed four distinct population segments of Atlantic sturgeon as endangered and one as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 2012.

In 2023, NOAA Fisheries celebrates the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act. Since it was enacted, no listed marine or anadromous species have gone extinct. However, as climate change intensifies, the recovery of listed species, like the Atlantic sturgeon and its relatives, may become more challenging. Through climate-focused research and management, NOAA Fisheries aims to mitigate the potential impacts of climate change on listed species to foster their continued recovery.

Impacts of Warming Water Temperatures

Atlantic sturgeon migrate from freshwater rivers and estuaries to the ocean as sub-adults, then return to spawn in the same rivers where they were born. Spring spawning adults move inland when temperatures warm and days are longer. Fall spawning adults move upriver in the heat of the summer to spawn as water temperatures cool in the fall. Due to climate change, the rivers and bays of the U.S. East Coast are warming earlier in the spring, and experiencing hotter peaks during the summer.

Juvenile Atlantic sturgeon prefer water temperatures between 65–72°F to develop, and they will be healthiest during years with that temperature range. Inland waters that warm faster and stay warm for longer due to climate change may limit successful spawning and threaten the survival of eggs and juveniles.

Spawning

As water temperatures increase in the spring and summer, sturgeon move inland to await optimal spawning conditions. During spawning, some sturgeon populations are sensitive to the number of daylight hours between sunrise and sunset. Ideal spawning conditions vary from population to population. For example, in the Chesapeake Bay, females release eggs on days with about 12 hours of light between sunrise and sunset in water temperatures between 70-77°F. As temperatures continue to increase, the day length cue for spawning that sturgeon follow may eventually occur when water temperatures are above 77°F. If these two drivers of spawning happen at different times, it could have detrimental effects on their reproductive success and survival.

Juvenile Development

Juvenile Atlantic sturgeon remain in the river where they are born for up to 6 years before migrating to coastal waters. For optimal growth and development, they need water temperatures between 64-71°C. Different sturgeon populations along the U.S. East Coast spawn in the spring or fall, depending on the water temperatures where they live. For young sturgeon born in the spring, the first few months of growth and development are critical for their survival through the hot summer months ahead. As water temperatures warm with climate change, young sturgeon lose valuable time seeking cooler waters rather than eating and growing.

Additional Threats

Climate change is causing water temperatures to increase earlier and stay high longer. Warming water temperatures in the spring and summer prompt sturgeon to move inland for spawning earlier than usual. This increased time spent in shallow inland rivers and bays raises their risk for impacts from vessel strikes, pollution, and other human-caused threats.

Climate change also amplifies the severity of existing threats, such as the loss of the hard bottom substrate that sturgeon rely on for egg deposition. This substrate became limited following widespread deforestation that began in the 1600s. As climate change impacts storm and precipitation patterns, resulting erosion and shifting sediment deposition will continue to alter and limit spawning habitat, activity, and success. These changes require sturgeon to spend more time searching for optimal spawning locations.

Other threats that sturgeon typically face, such as being caught as bycatch in commercial fisheries, can be more dangerous when combined with climate change impacts. Sturgeon bycatch in hot water is more likely to result in death due to the combination of the stress caused by the warmer temperatures and the stress of being accidentally captured. Dams amplify warming water temperatures in rivers and bays. These barriers limit upstream habitat availability and release increasingly hot water from reservoirs, artificially raising water temperatures downstream.

Recovery Efforts

The complex life histories of Atlantic sturgeon mean that continued research and monitoring of all distinct population segments is critical to understanding how to best conserve them. With our partners, we have taken steps to advance climate-focused science and management of their populations.

- We designated 3,698 miles of critical habitat for all five listed distinct population segments, including spawning and rearing areas and essential water features necessary for Atlantic sturgeon survival.

- Dam removal projects, like those on the Penobscot River in Maine and Rappahannock River in Virginia, have increased accessibility to upstream habitats

- We support the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s captive breeding and research programs that provide insight into the conditions necessary for the optimal growth, survival, and reproduction of Atlantic sturgeon

- The Students Collaborating to Undertake Tracking Efforts for Sturgeon program educates the public about sturgeon and the challenges they face

- International Cooperation via the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora protects Atlantic sturgeon and other sturgeons by regulating international trade in listed species of plants and animals

- Field research and population monitoring continues to advance recovery efforts as scientists learn more about Atlantic sturgeon behaviors and responses to climate change

- We are gathering and analyzing sonar data to help identify areas sturgeon use as habitat in the Chesapeake Bay.

You can help sturgeon recovery by reporting any sturgeon you come across. This allows scientists to better understand sturgeon populations, track recovery efforts, identify threats to the species, and fill in gaps in our knowledge. If you see a stranded, injured, or dead sturgeon, contact NOAA Fisheries at (978) 281-9328 or send us an email at noaa.sturg911@noaa.gov.

Responding to Climate Change

Shifting environmental conditions result in ever-increasing challenges for marine species. NOAA Fisheries is committed to our mission to conserve protected species in the face of the many threats posed by climate change. To prepare for and respond to these changes, we have launched the Advanced Sampling and Technology for Extinction Risk Reduction and Recovery program (ASTER3) to prevent extinction and promote recovery of protected species through transformational technological advances. We have developed the Climate, Ecosystem, and Fisheries Initiative to build ocean models and provide climate-relevant information that supports decision makers as they prepare for and respond to changing conditions. Additionally, we conduct:

- Climate vulnerability assessments for marine species to understand which species are most vulnerable and why

- Scenario planning to address uncertainties, predict impacts, and prioritize mitigation and recovery actions

- Climate-smart conservation training to educate staff on how to implement climate adaptation tools in their work

These initiatives strengthen our understanding of the impacts of climate change on protected species and their habitats. We will use this world-class science and data in our climate-informed actions to enhance species’ adaptations and resilience to changing conditions in the next 50-plus years under the Endangered Species Act.