The growth per molt of southern Tanner crab, Chionoecetes bairdi, is one of the key factors that determine the size of any individual southern Tanner crab. More generally, the growth per molt also helps establish the harvest potential of a crab stock.

In 2016. we captured immature male and female southern Tanner crab in the Bering Sea and transported them to Dutch Harbor. The crabs were measured and then held in individual containers both onshore and in hanging nets in the harbor. Twenty-one crabs molted and post-molt sizes were recorded.

While these additional data points are valuable to stock assessment biologists, further work is planned to provide more confidence in the growth estimates. This project was a cooperative effort of the NOAA Fisheries and the Natural Resources Consultants.

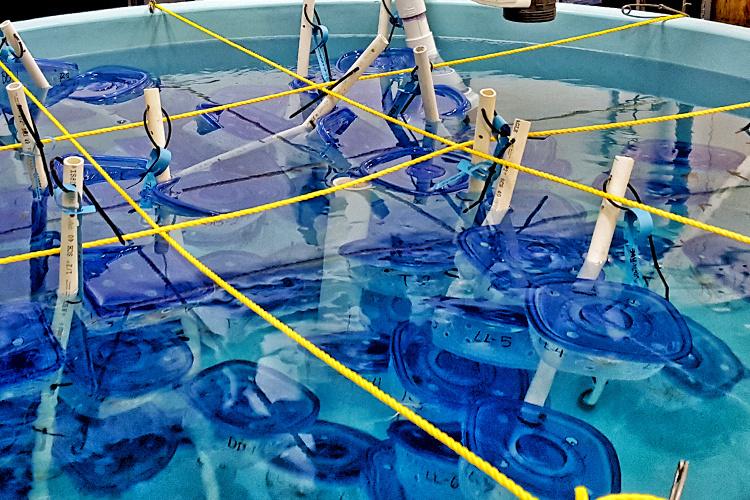

We repeated the growth experiment in the spring of 2017. This time, we brought immature male and female snow crab from the Bering Sea into our Kodiak Seawater Lab. The crabs were measured and held in individual containers inside the lab tanks.

Molting: How Crabs Grow

Crabs (and other crustaceans) cannot grow in a linear fashion like most animals. Because they have a hard outer shell (the exoskeleton) that does not grow, they must shed their shells, a process called molting. Just as we outgrow our clothing, crabs outgrow their shells. Prior to molting, a crab reabsorbs some of the calcium carbonate from the old exoskeleton, then secretes enzymes to separate the old shell from the underlying skin (or epidermis). Then, the epidermis secretes a new, soft, paper-like shell beneath the old one. The crab gradually retracts all of its body parts from the outer shell by a few millimeters, a process that can take several weeks, while it begins to secrete a new shell beneath the old one.

A day before molting, the crab starts to absorb seawater, and begins to swell up like a balloon. This helps to expand the old shell and causes it to come apart at a special seam that runs around the body. The carapace then opens up like a lid. The crab extracts itself from its old shell by pushing and compressing all of its appendages repeatedly. First it backs out, then pulls out its hind legs, then its front legs, and finally comes completely out of the old shell. This process takes about 15 minutes.

When a crab molts, it removes all its legs, its eyestalks, its antennae, all its mouthparts, and its gills. It leaves behind the old shell, the esophagus, its entire stomach lining, and even the last half inch of its intestine. After molting, The new shell is very soft at first, making the crab vulnerable to predators. Within a few days, the shell hardens up, and it becomes very hard after a month.

Crabs that have lost legs can regenerate them over time. The leg breaks off at a special joint. Before molting, a new limb bud, with all the remaining leg segments, grows out of the joint. After molting, the new leg is smaller than the others. The crab needs three molts to grow a leg back to its normal size.

Besides allowing the crab to grow, molting helps to get rid of parasites, barnacles, and other animals growing on the shell. It also helps to get rid of shells damaged by bacteria that degrade the chitin in the exoskeleton.