One of the first times I ever saw an underwater glider, it was suspended from a tree in New Jersey.

In fall 2017, when the AERD learned that we would transition away from ship surveys to glider surveys, we immediately reached out to the Rutgers University Center for Ocean Observing Leadership. Scientists and technicians there have been working with gliders for years, and they invited us to spend a week with them in their lab in New Brunswick, New Jersey to see what we were in for.

Mostly we just observed their technicians preparing gliders for deployment and tried to learn as much as we could. The one thing we helped with was a compass calibration.

Compasses are ingenious inventions. They work by detecting Earth’s magnetic field. A compass needle is also magnetic and can rotate freely, allowing it to react to and point towards Earth’s magnetic north pole. Although the compass is not the primary instrument the gliders use to navigate – they use a Global Positioning System (GPS) to navigate to specific waypoints – having a compass as a backup in case the GPS breaks ensures we can still steer and recover the gliders.

Because compasses react to magnetic fields, they can be thrown off in environments with lots of metal. Buildings are often constructed using lots of metal, so we can’t calibrate glider compasses indoors. At Rutgers, they suspend their gliders from a tree outside their lab. While suspended, the glider is slowly rotated 360o while horizontal, and also while held at angles that approximate diving and climbing. The glider’s compass readings are compared to a hand-held compass, and any deviations are noted. That way, if we have to navigate by heading and we instruct a glider to go east, we know exactly what direction it will go.

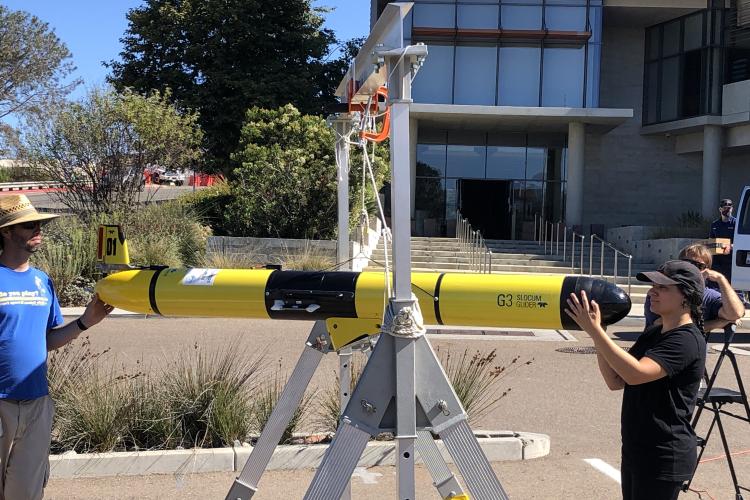

At our lab in La Jolla, we don’t have any nearby trees that can bear the weight of a glider. Instead, we suspend our gliders from an aluminum gantry in our parking lot (away from cars). Aluminum is not strongly magnetic, so it doesn’t throw off the compass.

I always look forward to Compass Calibration Day – it’s the best part about preparing gliders for deployment. We need several people to help hoist and rotate the gliders safely, so we each bring snacks to share and we play music and have a good time. We also enjoy the puzzled looks we get from drivers on the busy coastal road outside our lab as we spin these giant yellow torpedo-looking things in the air. Some people even stop to watch and ask us what we’re doing, and we’re always happy to explain.

It’s those moments – when we’re having fun with each other while doing science and we can share that with onlookers – that remind me that even when gliders are stressful, they’re cool.